One point that’s come up a couple of times is the expense of imposing serious infection controls. China probably lost hundreds of billions of dollars on controlling the outbreak in Wuhan. Let’s try to make a guess of how much it would cost us, and use that to figure out what the best path forward is.

For starters, let’s take some reference points. Assume that completely uncontrolled, the R0 for the virus is 2.0. This probably incorporates small personal, relatively costless changes like better handwashing, sneeze and cough etiquette, etc. Evidence from China suggests that their very strong controls brought the R0 down to about 0.35. We’ll assume that those level of controls mostly shutdown the economy, reducing economic activity by 90%. U.S. 2019 GDP was about $21.44 trillion, so we can estimate the daily cost of these extremely stringent controls in the U.S. as being about $50 billion.

Next, we’ll guess that the daily cost of imposing controls gets harder as you go lower – it’s not linear in R0. Instead we figure that every 1% reduction in R0 costs the same amount. So, to drop R0 from 2.0 to 0.35 we estimate would cost about $50 billion, and thats 173.42 1% reductions, so each 1% reduction would cost about $288 million dollars per day. There’s one other thing to keep in mind for cost accounting: it’s much, much cheaper to impose controls when the total number of infections is low. In the low regime, you can do contact tracing and targeted quarantine rather than wholesale lockdowns. So if the total number of infections in the population is below 1,000, we’ll divide the cost of controls for that day by 500.

Finally, we need to balance the costs of infection controls with the benefits from reduced infection and mortality. All cases, including mild, non-critical cases, cost personal lost income: about $200 a day (median income of ~70K, divided by 365). For critical cases in the ICU, about $5000 a day For critical cases in a general hospital bed, about $1200 a day. For critical cases at home, no additional marginal cost. Deaths will cost $5 million.

Now we can make a back of the envelope estimate of the costs and benefits of different courses of infection control.

We’ll impose infection controls on day 130, when there’s 30 dead and 30,500 infections out there. Then we’ll sweep through different strengths of controls and see what the total costs look like over the whole course of the epidemic.

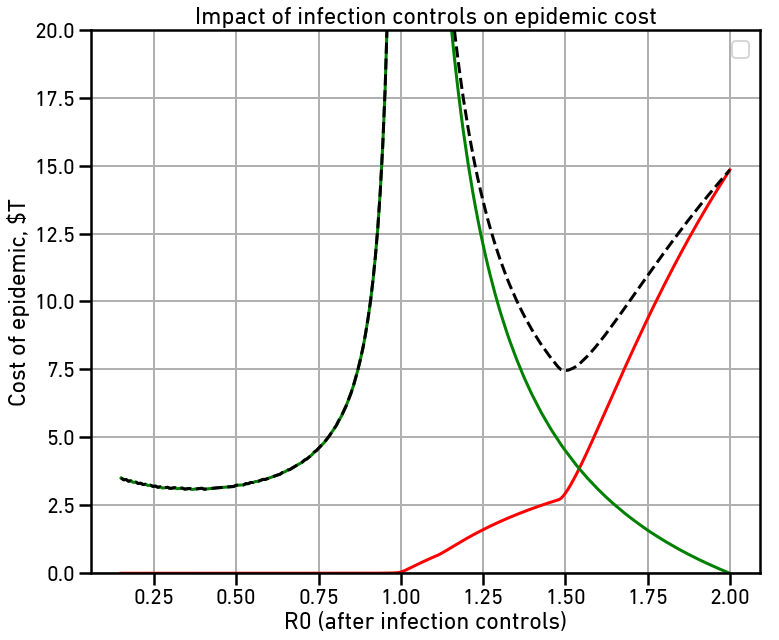

The red line is the cost of the disease itself, largely due to deaths. The green line is the cost of maintaining infection controls throughout the epidemic. The dashed line is the total cost, all in billions of dollars. Note that with no controls, our estimate of the total cost to the US is $14.8 trillion dollars, or about 2/3 of the total US GDP.

There are two local minima on the total cost curve. The first is right around R0=1.50. This makes the spread slow enough that hospital capacity is never overloaded, greatly reducing the number of deaths and thus the cost of the disease. This reduces total cost to $7.45 trillion dollars, just about half of what the uncontrolled cost would be. Note that even with this small amount of reduction, the majority of the cost is due to the controls rather than directly due to the disease.

The second local minima is at the far left, right around at R0=0.35, or about what the Chinese managed in Wuhan. This slows the spread of the disease so fast that we rapidly enter back into the much cheaper contact-tracing regime where wholesale lockdowns are no longer necessary. This reduces total cost to $3.11 trillion dollars, half again the cost with only moderate controls.

The cost savings with very serious controls imposed as soon as possible comes from two sources: First, lower disease burden in deaths, hospitalization, and lost productivity. Secondly, it’s cheaper to impose very serious controls because they need to be imposed for a much shorter period of time to control the disease.